As 2001 came to an end, it was almost time to celebrate my one-year anniversary of moving to Buenos Aires. I’ll be the first to admit that I was slow in coming to terms with some of the quirks of Argentina. But I was about to learn more than I bargained for.

After the establishment of the corralito, everyone knew bad times were ahead. And messing with people’s income is a sure way to get the public irritated. However, the only visible sign of the impending crisis was the bad attitude that almost everyone carried around like a huge weight. Perfect time to learn a new bit of Argentine slang: cara de culo or assface. No further explanation required. Short tempers prevailed along with many bad comments about the government… a normal reaction to the events of the past few months.

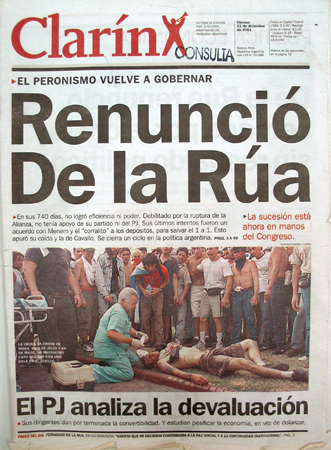

Outside the city, things were changing more rapidly. Looting of supermarkets and a few riots took place, mainly in the southern suburbs of Buenos Aires. Some of it was spontaneous and some of it was “sponsored” by the Peronist party that wanted to get President De La Rúa out of office. Political parties in Argentina are known to pay people to demonstrate, make a show of public support, or do whatever is asked of them. Regardless, news coverage of these events brought to mind Alfonsín-era hyperinflation… nothing pleasant. After several consecutive days of suburban problems, looting spread to the city itself & the President announced that he would make a televised speech on December 19th.

Since televised public addresses aren’t that common in Argentina, everyone seemed anxious to hear what he would say. As the speech was set for 21:00, I had time for my regular evening walk around Caballito. I used to take frequent walks mainly to escape from our small apartment, get a little exercise and check out my barrio. After walking only a few blocks, I could tell something was going on. It was a typically hot and humid December evening, but people were even more pissed than previous days. Everyone had this vibe of irritability just waiting to explode. Although it sounds like I put this together with the benefit of hindsight, I distinctly remember coming home from my walk and telling Fabio that there was something strange in the air.

21:00 and the sun had just set. The President spoke briefly, informing the public that due to increased criminal activity a state of emergency would exist indefinitely from that moment. What?! Give the police free reign to do anything they want? Were there enough lootings to justify such a radical measure? My thoughts raced between, “we’re fucked” to “damn, this is exciting.” How many people get to witness dramatic political change on this scale? Apparently I wasn’t the only one to think the situation was screwed. Within minutes of ending the address, Fabio and I began to hear noise outside. People were out on their balconies, banging away with whatever they could find. As more heard the clamor, more joined in. Passing cars began honking their horns in support.

I understood what all the racket meant because it had happened a couple times in the previous week. Fabio explained that it was a form of public protest, non-violent in nature, that originated during the last days of Alfonsín. The cacerolazo allows people to let off steam, make their disapproval heard, and get on with their lives. At least that’s what had happened previously. Fabio went out on the balcony to add to the noise, and I didn’t think much of it. After all, I was a foreigner living in Argentina without a visa & my money wasn’t locked in the bank. If things got really bad, I could always leave. So what right did I have to join in the protest? I’m trying to decide what to do when it occurs to me that it won’t last long so it doesn’t really matter anyway. Previous cacerolazos had ended after about ten minutes. This time was different. Fifteen minutes go by & instead of dying out, it gets louder. Thirty minutes. Louder. Forty-five minutes & Fabio and I notice that people are leaving their apartments and taking the protest to the streets. People are in the middle of the streets, blocking traffic, and they’ve brought their pots and pans with them. You can make a LOT of noise with a pot and a wooden spoon. Try it at home.

By this time, I had come to the conclusion that the person I love & my newest friends had been unfairly affected by government decisions, so why not protest? I was a bit stressed by the situation too –-not knowing whether I would be able to get money from any ATM and not having a cash backup. My income wasn’t in jeopardy, but I was far from living comfortably. So we go down to the corner and join in with the rest. At that time, we lived only one block from the major intersection of Avenida Rivadavia and Avenida La Plata. Over the next few hours, traffic came to a complete halt. At most intersections, trash bags and bins had been piled up and a few set on fire. That was enough to persuade people to stop driving. All the time, more and more people came down to protest. I’d never seen anything like that before. It was completely spontaneous, non-violent, and mainly middle-class. To add spice to the banging of pots and pans, certain slogans were repeated especially: el pueblo, unido, jamás será vencido… another reminder of Alfonsín days. Everyone in Caballito had had enough, and they needed to voice their opinions.

As the evening progressed and protests showed no signs of diminishing, Fabio and I began to see small groups of two to twenty people walking down Avenida Rivadavia towards the center of town. Avenida Rivadavia more or less bisects Buenos Aires into north and south and begins in Plaza de Mayo at the Casa Rosada. Everyone was going there. We lived at the 4700 block of Rivadavia which equals 47 city blocks from the center. Fabio wanted to start walking, thinking that we wouldn’t get any farther than Once at the 2800 block. As a huge public square, it was a logical place for the police to set up a barricade if they wanted to stop protests from spreading. But as of yet, we had seen no police intervention and from period trips to the apartment to check local tv coverage of events, nothing other than lots of making noise had occurred. So off we marched.

It appeared that everyone had the same idea. As we were to find out later, there were basically three columns of people marching towards the center: from the north along Avenidas Santa Fe and Córdoba, from the center along Avenida Rivadavia and from the south along Avenidas Independencia and San Juan. I really didn’t know how far we’d actually go but it seemed like a good idea to me and we were caught up in the moment. It was emotional for me, to say the least. I had heard everyone bitch and complain about the situation for months and finally action was being taken. And it wasn’t the elite or the poor who were paid to demonstrate. It was people I could identify with. As we marched towards Once, I remember looking at everyone’s relief while they chanted, “Cavallo is a son of a bitch! Step down, De La Rúa!” I remember looking at older women out on their balconies at 01:00 banging on their pots and pans, cheering the people who were walking to Plaza de Mayo. Most of all, I remember thinking that something like that would NEVER happen in the United States of 2001, War on Terror or no.

To our surprise, Once was only full of protestors and no police. So we kept on marching along with everyone else & reached Plaza de Mayo around 01:30. We were some of the first to arrive because although the Plaza was full, it wasn’t packed with people. Walking toward the Casa Rosada, we saw a barricade had been erected and a single row of police guarded the presidential office. That was about it. Fabio and I laughed as we looked at the pan we could never use again. Searching for a spot to rest, we managed to find a little bit of grass right next to the CNN camera crew. They were just standing by idly, watching everyone continue to make noise, with the camera off and resting on the ground. I guess it wasn’t interesting enough to film a peaceful protest.

After walking almost 6 km, I was beginning to think, “Ok, we made it. Now what?” We didn’t have to wait long. First we heard that Domingo Cavallo had resigned as Economic Minister. So much for that Nobel Prize he desired. There had been a large group of protestors concentrated outside of his residence for hours. Part of the battle had been won. But suddenly I saw the CNN guys pick up the camera and start rolling. What was going on? As I scanned the plaza, I saw tear gas canisters being shot by the police from the northeast corner right into the middle of the square.

As canisters flew, a mass of people in wave motion evacuated that corner of the square. Evidently someone had harassed the police too much. Fabio and I managed to get tear gassed along with pretty much everyone else. We retreated to a side street, covered our faces with our t-shirts & decided to head home. Fabio gave good advice. He said that the police could easily take advantage of a small disturbance, break into businesses themselves, create havoc and later say that the public got out of control and shift the blame. I had been in Argentina long enough to know that this was definitely possible. So we left Plaza de Mayo. But there were thousands of people who were still arriving that hadn’t heard about Cavallo and that hadn’t seen the police tear gas anyone. We walked part of the way back and managed to find a taxi on the back streets to take us home. We went to bed sometime after 03:00 with protests still in full swing.

Ten years later, I still consider that evening a defining moment in my life. Not because I thought Argentina would suddenly develop a new-found sense of civil society & the future would be radically different; this was more personal. I’d spent the last year fairly insulated, learning how to be a tour guide, getting to know new destinations in Europe, & hadn’t paid much attention about what was going on in my own backyard. December 2001 changed that. Very few people were blogging at the time, but through a free website I started writing about what was happening in Argentina. My exploration of BA began in earnest then, which developed into guiding tours in BA & eventually morphed into Endless Mile… the unexpected silver lining from an emotional & turbulent summer evening in Buenos Aires.

Dear Robert you account is a truthful and accurate and almost coincides with my own recollections in Caballito that night.

You will soon be able to experience something similar in Portugal and Spain… regretfully. It will be different in form but the cause of these crisis is the same here there and everywhere.

Love

Estela

PD You are always in my line of thought when I walk attentive in my neighborhood

Thank you, Estela! That evening was such an incredible time, for many people & for many reasons. There was a palpable sense of change in the air but not violence. Remarkable. Europe certainly isn’t doing well, especially when the same politicians continue to make the same mistakes. We’ll see where the future leads… I miss Caballito! I’m in Recoleta now, not far from the cemetery but I definitely prefer Caballito 🙂