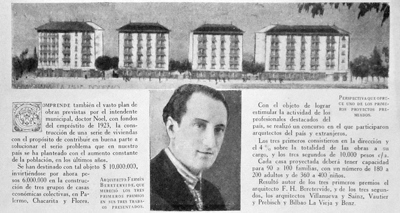

One architect stood out among all others during the era when social housing projects were being built in Buenos Aires. Due to political beliefs, he was ostracized from the academic community & died in obscurity in 1979. Only since his death has he been given the attention & recognition which he deserves…

Fermín Bereterbide graduated from the Universidad de Buenos Aires in 1918 & immediately began changing the urban landscape. In fact, he was one of the city’s first urban planners… someone who believed that the structure of the city itself determined the quality of life for its residents. Always innovative, one of the constants in Bereterbide’s career was the belief that housing projects for the underclass were very beneficial to the city. Take care of your poor & everyone benefits. Pretty simple.

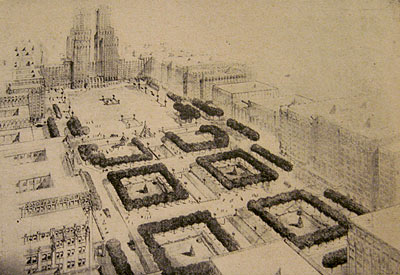

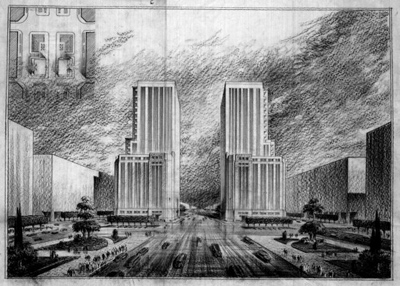

Bereterbide won a number of city contests for housing projects & had many of them built in the 1920s, but it was his urbanistic views which generated controversy. Actively participating in architectural digests, city government planning organtizations & other local committees, Bereterbide took every opportunity to make his opinions public. For example, when he lost the contest for the development of Avenida Norte-Sur (today known as Avenida 9 de Julio with its large obelisk), Bereterbide continually protested the avenue’s current look. He wanted an underground vehicle tunnel built for speed while ground level was to become a core for government offices & parks. Even though I like the obelisk, his plan would have been more functional & definitely more beautiful than what is there today.

With the 1934 booklet “What is Urbanism?”, Bereterbide drew examples from all over the world in order to convince local architects that urban planning on a broad socio-economic scale (even including Gran Buenos Aires) was necessary to improve everyone’s quality of life. His quote from a 1939 city government bulletin says it best:

What is lacking is not money, land or demand; what we’re missing (& this is where the problem lies) is a notion of humanity, trust in those concerned about this issue & the will to make things happen.

When an earthquake destroyed the city of San Juan in 1944, his plan to construct an entirely new city (instead of just rebuild what had collapsed) drew a lot of criticism. Not accepted, it was the beginning of his downfall. Very anti-Peronist in his politics, Bereterbide refused to acknowledge President Perón at an award ceremony given for a project he had won. Later, he spent time in jail for his political beliefs & was even kicked out of his professional organization, the Sociedad General de Arquitectos. One major housing project was built in 1955 with Bereterbide all but disappearing after that.

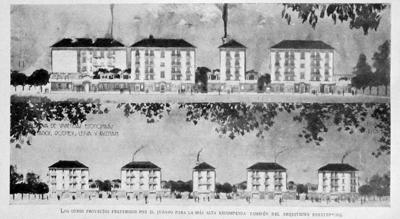

Leaving behind an important legacy, Bereterbide’s housing projects—those built & those never constructed—will be the topic of the next posts in this series. La Ciudad Se Transforma documents improvements in the city during the period of 1922-28 (when President Marcelo T. de Alvear appointed Carlos Noel mayor of Buenos Aires) & demonstrates Bereterbide’s influence. He won the top three prizes in a housing project design contest, destined for Palermo, Chacarita & Flores. From the sketches, these designs are similar to Barrio Los Andes & La Masión de Flores (both discussed in detail next). I wonder whatever happened to the Palermo project… the base for the contest was to house 90-100 families in each project, with total capacity for 180-200 adults & 300-400 children:

Sources: Boletín del Honorable Concejo Deliberante, 1939 • ¿Qué es el Urbanismo? by Ernesto Vautier & Fermín Bereterbide • Diccionario de Arquitectura en la Argentina published by Clarín • Historias de la Ciudad, Año 3, #14 • La Ciudad Se Transforma, scanned by Historia Digital.

Direct link → Master list of all Housing for the Masses posts.