In 2013, the following article appeared as a two-page spread in the Autumn/Winter edition of Time Out: Buenos Aires. When the editor first contacted me to write about BA architecture, the only thing that ran through my mind was “1400 words?!” Somehow I managed to fit history, architectural styles, recommendations & current events in that limited space. They had to remove a couple of my listings to make the article fit, but I’ve put them back in this post.

Several of my photographs also accompanied the text, but here I can add more. As always, larger versions of many photos in this post can be found on Flickr. I’m thrilled Time Out thought of me for this piece, & I had fun working with them. All those long walks in Buenos Aires & posts about architecture paid off.

A guide to Buenos Aires architecture

Architecture buff Robert Wright uncovers the city’s finest monuments & hidden gems

Ask any expert to describe Buenos Aires architecture and guaranteed the word “eclectic” will crop up. The city’s buildings, the work of architects and construction crews who hailed from all corners of Europe, reflect the very history of BA: its rises and falls are written all over the domes of Beaux Arts palaces and the concrete exteriors of modern skyscrapers. To understand BA’s architectural mix, here is a roundup of the styles and buildings you can expect to see while meandering through the streets.

Colonial style

River views may have been ideal for keeping watch on potential invaders, but a city in the grasslands had no stone available for building. Adobe and straw, then brick, became the building blocks of early Buenos Aires; consequently, very little from this era has withstood the test of time. The longest-lasting reminder of Spain harks back to the city’s religious roots. Major Catholic orders —Franciscans, Dominicans and Jesuits— were given one city block each to develop, and their trio of churches sits just south of Plaza de Mayo. The white Iglesia de San Ignacio (Bolívar 225) is the best of the bunch, with threatening structural cracks recently restored. The Baroque church was consecrated in 1734 and is said to be the oldest building in town. Get a homier feel for colonial days at the Casa de Virrey Liniers (Venezuela 469), where the former viceroy accepted British surrender after a failed 1806 invasion.

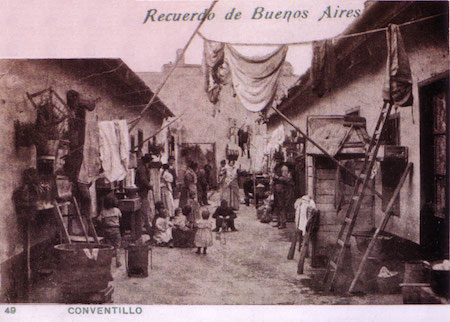

Casa chorizos and conventillos

Lack of stone translated into homes that were built long and low. Narrow lots produced a particular style of house: rooms sat one behind the other in linear fashion accessed by a long, skinny passage running down one side —just like a sausage (chorizo). After independence in the early 19th century, Buenos Aires grew at a snail’s pace, with the casa chorizo a typical feature of San Telmo.

Elite families built their mansions in central and southern sections of the city until an 1871 yellow fever epidemic sent them packing north. Old homes sold at bargain prices, and developers rented rooms to newly-arrived immigrants. Patios became playgrounds, laundry hung to dry everywhere and single men often slept four to a room. Renamed conventillos, rooms in these “little convents” mimicked a cramped monk’s cell. Many survive, open to the public, like the former Ezeiza family home (Defensa 1179).

Beaux-Arts

European immigrants began arriving by the boatload after 1880, filling conventillos, while the upper class strived to imitate the undisputed capital of European culture: Paris. Architects studied abroad and returned to inject Buenos Aires with some much needed joie de vivre. During this era, Avenida de Mayo opened the middle of a city block and broke through the restrictive grid plan. Take a stroll and find the few Parisian elements that remain —look for sloped, slated rooftops and decorative domes, especially between Calles Esmeralda and Suipacha.

A few blocks away in Tribunales, the 1908 Teatro Colón (Cerrito 628) remains the fanciest public building of the era, constructed completely of imported materials.

But it was the city’s private residences that truly reflected French luxury. Modern development has erased many of these elite mansions, but a few survive as embassies or museums. Plaza San Martín majestically guards two: the Palacio Paz (Avenida Santa Fe 750), home to founders of the first big local newspaper La Prensa, and the Palacio Anchorena (Arenales 761), former home of wealthy landowners now used as a foreign affairs office. At the beginning of swanky Avenida Alvear in Recoleta, the Palacio Ortiz-Basualdo (Cerrito 1399) fittingly houses the French embassy. It opens to visitors just one day a year in mid-September.

Art Nouveau

As the elite grew richer during an economic boom at the beginning of the 20th century, hard-working immigrants also improved their standard of living. Moving out of crowded conventillos, they speculated in real estate and added to their wealth.

Up-and-coming families constructed large apartment buildings for their own residences, and rented other units inside for a handsome profit. These buildings adopted the latest trends from Europe, and art nouveau in Buenos Aires often equates with nouveau riche. Highly visible areas like the façade and foyer received lavish decoration.

Peacocks, cherubs and bare-breasted women adorn architect Virginio Colombo’s Casa de los Pavos Reales (Rivadavia 3216) and the Casa Calise (Hipólito Yrigoyen 2562) —both in Once.

Argentina also adopted Art Nouveau for its centennial celebrations in 1910. As a result, many public and private buildings built shortly afterwards are glorious examples of the style. In the city center, don’t miss the shopping/office space Galería Güemes (enter on San Martín 170 for the original façade) or the other big gallery in town, the Palacio Barolo (Avenida de Mayo 1370). In the latter, snakes and dragons decorate what architect Mario Palanti designed to be the final resting place for Dante Alighieri’s ashes. A vision of Dante’s cosmos, the entrance gallery is a much nicer version of Hell and is topped by offices in Purgatory (anyone who’s been stuck in the Palacio’s wooden lifts has had a taste of what Purgatory must feel like). The revolving beacon at the top of the building represents Paradise.

Another of Buenos Aires’s must-see Art Nouveau gems is the Edificio Otto Wulff (Avenida Belgrano 601) in San Telmo, built on request by shipping magnate Nicolás Mihanovich. Danish architect Morten Rönnow adorned the façade with native flora and fauna; giant condors gaze down on a much busier city today than when built in 1914.

Finally, next to the Congress building and just three blocks from the Palacio Barolo, the Confitería del Molino (Rivadavia 1801) —with a ground-floor coffee house sadly closed since 1997— is an Art Nouveau phoenix waiting to be reborn.

Mid-century

Overblown Art Nouveau fell out of fashion quickly. After World War I, Europe embraced the Machine Age and geometric designs and straight lines replaced curves and swirls. In BA, architect Alejandro Virasoro became Art Deco’s biggest proponent, constructing dozens of blocky buildings like the Casa del Teatro (Avenida Santa Fe 1243). Theaters grew in popularity during this time, and the futuristic Teatro Ópera still thrills spectators (Avenida Corrientes 860).

Racionalismo, also called Streamline Moderne, took the city by storm and ultimately became more popular than Art Deco. Decoration both inside and out was kept to a minimum, with clearly defined volumes becoming the only decorative feature. Buildings with rounded balconies and doors with circular, porthole windows often resemble ships plowing through the city. A trio of buildings sums up this style: the office blocks Edificio Comega and Edificio Safico (Avenida Corrientes 222 and 456) and the luxurious apartments of the Edificio Kavanagh (Florida 1065).

Racionalismo may have been another European import, but with neocolonial influences, architects attempted to define a pure Argentinian style, combining indigenous imagery with Spanish design. Many neocolonial buildings are museums today, such as the Museo Enrique Larreta and Museo Yrurtia in Belgrano (Juramento 2291 and O’Higgins 2390), the Casa de Ricardo Rojas in Recoleta (Charcas 2837), and the Palacio Noel in Retiro (Suipacha 1422). A refit of the much-maligned Cabildo on Plaza de Mayo dates from this era as well, feigning to be from the city’s colonial past.

Modern times

The 1960’s and 1970’s proved unkind to architectural heritage in BA. Many masterpieces were demolished to make way for high-rise buildings. The city briefly flirted with concrete-heavy Brutalism, with Clorindo Testa’s Biblioteca Nacional (Agüero 2502) as the most outrageous example. In Palermo and Belgrano, quaint streets of individual houses were replaced with densely populated apartment towers. A vacant area downtown housed the first concentration of modern office buildings (Catalinas Norte). Shortly after, nearby Puerto Madero caught the bug, with previously abandoned swaths sprouting high-rises. Today, most of the tallest buildings in BA can be found in Puerto Madero. The current king is the Torre Renoir II (Marta Lynch and Aimé Painé) at 175 m and 50 storeys, completed in 2010.

Encroaching on its crown is the residential Alvear Tower, currently under construction, with plans to reach 235 m with views of Uruguay when completed in 2015.

The best way to appreciate different styles of BA architecture is on foot. Find your inner flâneur, look up from the uneven sidewalks and discover the variety within this unique, eclectic capital city.

Demolishing history

Visitors rave about BA’s buildings, but the local government gives architectural heritage little more than lip service. In 2007, city officials passed a temporary law protecting all structures built prior to 1941. Renewed every two years thereafter, mayor Mauricio Macri —whose family made millions from construction— hoped the law would expire unnoticed, just before his second term began in 2011. He couldn’t have been more wrong.

Citizen activist groups managed pressure legislators to pass the law again. But enforcing it has proved more of a challenge. Clandestine demolitions occur all too frequently, with crews sneaking in at night to remove everything of resale value. Windows are sometimes left wide open so rain damage makes restoration impossible. Real estate developers certainly have more tricks up their sleeve, but Buenos Aires manages to fight on.

Keep in mind that the above article is a basic intro for all the wonderful architecture in Buenos Aires. With each economic boom, porteños latched on to a trend & ran with it. They also had 203 square kilometers (78 square miles) to build in. During 12+ years of living there, I was able to walk an estimated 75% of the city. What a great time! Remember that I got hooked on researching early housing projects (from 1910 to 1950), finding as many buildings as possible by Estanislao Pirovano & even wrote a guide to Art Nouveau in Buenos Aires, with 75 of my favorites buildings from that era. The list of great architecture in Buenos Aires goes on & on… share your favorites with me!

He leído su artículo sobre construcciones de Buenos Aires. Me ha parecido interesante, a pesar de las limitaciones a las que estaba obligado. Le cuento que desde hace tiempo. Voy registrando la gran cantidad de cúpulas, cariátides, atlantes y dos pares de autómatas que se observan en las alturas de la ciudad. Construcciones realizadas casi todas a fines del siglo XIX y principios del XX. Llevo contabilizadas mas de ciento veinte y sueño poder algún día fotografiarlas desde ángulos poco acostumbrados. Como ser desde otros edificios altos o mediante drones.

Atentamente Lic. Luis Jaime Burmeister.

Hola Luis – Genial el proyecto tuyo… si llegás a sacar las fotos, avisáme. Tengo una serie de fotos de más de 150 cúpulas de Buenos Aires, 75 están reunidas acá en está página. Espero poder subir todas las fotos pronto. Saludos!

Are your Buenos Aires architecture guidebooks available for purchase? Thank You

Hello, Richard – If you go to the main page of this website, you’ll see all my guidebooks. The only specific architecture guide for Buenos Aires is Art Nouveau, but all of my guides discuss architecture. If you have any other questions, please let me know. Take care.