First off, a disclaimer. I probably should have read this book in Spanish. I loved “Don Segundo Sombra” & “Radiografía de la Pampa” in their original versions, but after struggling with gaucho terminology & words that most Argentines today would not recognize, I decided to see if there was an English translation available. Not only did Amazon have it, but everyone raved about the translation. And it was annotated!! “A Visit to the Ranquel Indians” has been waiting patiently on the bookshelf since January…

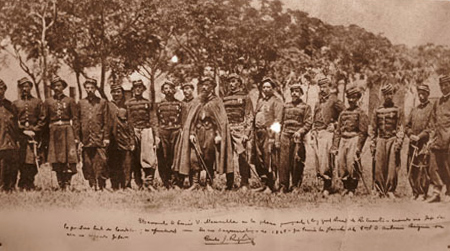

Author Coronel Lucio V. Mansilla (pictured in center above) requested a very particular assignment: to be sent as a diplomat on behalf of the national government in indigenous territory to defend a signed peace treaty. [For a detailed biography, head to my sister website AfterLife… Mansilla is buried in Recoleta Cemetery.] His successful mission lasted 18 days in 1870, & he later wrote about the experience for a Buenos Aires newspaper La Tribuna. Colloquial in style, Mansilla’s 68 installments appeared as if they were letters to his friend, Santiago Arcos, in Madrid. The 1997 version I read consists of 385 pages with an additional 80 pages of notes. You can imagine the detail.

The translation by Eva Gillies transmitted the spirit of the coronel nicely even if some English words were obscure. Annotations proved to be essential, explaining long-forgotten literary references, historical figures or customs. The introduction has the best 20-page explanation of the Rosas era I’ve ever read. Hands down. But placing all annotations at the back of the book instead of on the same page was a big editorial mistake. Although I did it, flipping back & forth 2-3 times per page of original text got old fast. Sometimes Gillies explained obvious or unnecessary items; however, erring on the side of thoroughness isn’t much of a complaint.

On with the story…

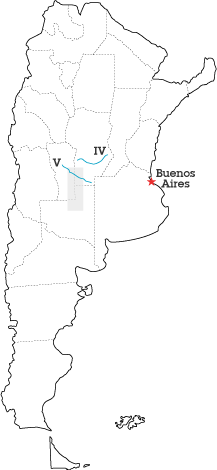

Mansilla’s collective essays offer a rare opportunity to explore the mindset of a well-traveled & well-read, upper class army officer. After all, he was the nephew of Juan Manuel de Rosas. But also we get a priceless ethnographic study describing a people & customs that no longer exist. Mansilla took his troops with minimal weapons south of the Río Quinto (Fifth River, marked on the map below with a “V”) to meet the Ranqueles, a tribe of Araucanians settled in what would eventually become parts of the modern provinces of Córdoba, San Luis & La Pampa. His excursion corresponds to the shaded area below:

Beginning slowly, Mansilla describes the terrain with military precision while commenting on plant & animal life. His substantial wit pervades the entire text. Mansilla also offers the reader numerous opinions about a wide range of topics: current events, old age, freedom & rights, travel, nation building, socialism & solidarity, even dancing! Attempting to rebuke some of Sarmiento’s 1845 work “Facundo: Civilización y Barbarie,” he enjoys questioning previously accepted notions of civilization. Imagine that… a dandy calling into doubt his own existence. He also revels in talking about himself, often with a touch of satire that makes his introspection amusing rather than arrogant.

Woven throughout the entire book are several asides: mini-biographies or life stories of men that Mansilla encounters along the way. Of note are:

- Corporal Gómez – a soldier who bravely fought with Mansilla in Paraguay, thought dead, who reappeared from nowhere then was executed for a crime committed under the influence of alcohol.

- Mariano Rosas – a Ranquel captured by Juan Manuel de Rosas (hence the last name) who later escaped & became an important chieftain.

- Miguelito Corro – in love with two women, married one while keeping the other as a mistress & gets into all sorts of trouble.

- Doctor Macías – the miserable secretary of Mariano Rosas who lived with the tribe because he had no means of escape.

Although at times distracting, these glimpses of frontier life through others add atmosphere to the story & show that Mansilla indeed cared about the men under his command.

Mansilla describes tribal life at length. We learn how the Ranqueles get married, their customary thievery, seeming endless drinking (yapaí!), how a few hundred Christians came to live with different tribes & their willingness to accept certain Catholic rituals supplied by two Franciscan priests who accompanied Mansilla. He admits to the reader that another of the excursion’s main goals was to get local tribes to cede land for the building of a transcontinental railroad. Sneaky. But Mariano Rosas is not easily fooled.

Some of the most intriguing exchanges deal with land claims:

“I explained that land belonged only to those that made it produce; that the government was purchasing from them not the right to it but the possession, recognizing that they had to live somewhere.

He argued the past, saying that in other times the Indians had lived between the Ríos Cuarto and Quinto, and all that country was theirs.

I explained that the fact of living or having lived in a place did not constitute dominion over it.

He argued that, if I were to settle among the Indians, the piece of land I would occupy would be mine.

In reply, I asked him whether I could sell it if I felt like doing so.

This question did not please him, because it was difficult to answer…”

The obsessive dislike of an accordion player —a black man who was a sort of court jester for Mariano Rosas— grew tiresome & failed to provide the comic relief Mansilla likely intended. And the overly long descriptions of infinite greeting & farewell ceremonies put me to sleep… as I believe it did Mansilla. At least we know exactly how he felt! Certain passages were too verbose; then again, this was written as a newspaper serial & not initially intended as a book. In all, minor issues compared to the valuable insight the work provides today.

In the end —in spite of Mansilla’s successful visit— the indigenous population of Argentina would pay a high price a few years later. Hunted down with superior firepower, the Conquest of the Desert confiscated large amounts of land for Argentina’s upper class while imprisioning or killing its original inhabitants. “A Visit to the Ranquel Indians” manages to rescue an important moment in time while entertaining its readers. We owe Mansilla a great deal for that.