Working with tour groups in Spain, the question of Catalan independence comes up frequently. I do my best to try to explain the issue as concisely & fairly as possible, but this topic truly challenges condensation. Here’s my take.

Creation

The 711 invasion from North Africa indirectly gave birth to Catalunya. In just five years Muslims conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula with little or no opposition, so why stop there? Troops pushed north to occupy Carcassonne & Provence, even sending expeditions as far as Dijon by 725.

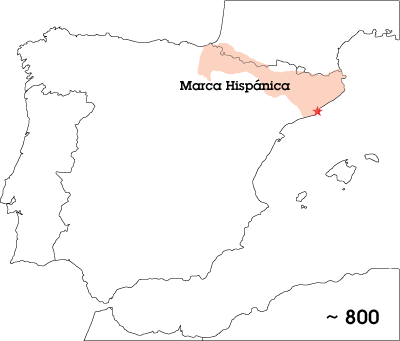

The Franks, ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, took notice & decided to intervene. Under the reign of Charlemagne, Barcelona returned to Christian rule in 801 & helped consolidate the Marca Hispánica… a line of several territories south of the Pyrenees set up as a defensive border. The newly-titled Count of Barcelona remained a vassal of the Carolingian king. No independence yet. But in 878 Guifré el Pelós (Wilfred the Hairy) managed to establish hereditary succession, removing a bit of authority from the Franks.

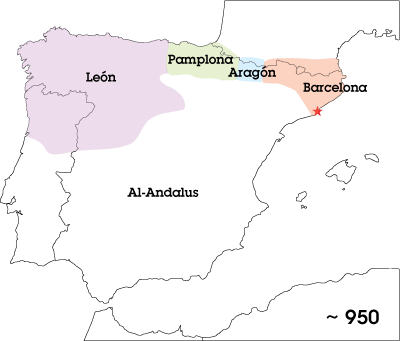

Fast forward 100 years & the County of Barcelona once again came under attack from their Moorish neighbors to the south. Frequent battles plagued the area with Aragón & Pamplona also fighting the Moors. Unfortunately for Barcelona when times got tough, the Franks failed to send support. To be fair, the Capetian dynasty had just claimed the Frankish throne so they were occupied with internal affairs. But their lack of assistance generated resentment. Barcelona suffered a brutal attack in 985 but later took advantage of a Moorish power vacuum to begin their own raids. The caliphate of Córdoba broke into mini-kingdoms (taífas) in 1031, & Barcelona’s power began to grow.

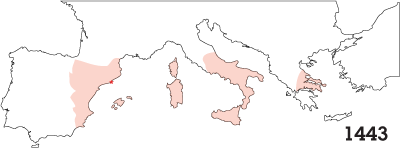

Count Ramón Berenguer III (r. 1113—1131) had more going for him than just being El Cid’s son-in-law; he expanded territory inland & throughout the Mediterranean. Ramón Berenguer IV married Petronilla of Aragón & merged early Catalunya with the Crown of Aragón. Their son, Afonso II, became both King of Aragón as well as Count of Barcelona although territories remained separate entities… similar to a confederation. Other Christian neighbors became more powerful at the same time, so conflict often broke out among everyone. Muslims were not the only enemy.

The 1258 Treaty of Corbeil finally gave the County of Barcelona formal independence from France during the rule of Jaime I. His son expanded the reach of Aragón far into the Mediterranean & became King of Sicily as well as ruler of Athens. Remember officially we’re talking about the Crown of Aragón here & not Barcelona or Catalunya.

In 1412, the last Count of Barcelona died without an heir. After an agreement between concerned parties, all titles & power transferred to his grandson, Ferdinand I of the Castilian House of Tratásmara. Three generations later, the marriage of Ferdinand II (King of Aragón) to Isabel (Queen of Castilla) —los Reyes Católicos— consolidated power away from Catalunya. Their descendants continued to centralize government with the new nation of Spain taking precedence over smaller kingdoms or principalities within its borders.

When Catalan peasants were forced to house national troops during the Thirty Years’ War (1618—1648), local leaders felt the Spanish crown abused its power. The resulting Reapers’ War (1640—1652) is cited by many as Catalunya’s first attempt to become independent from Spain. Although proclaiming the Catalan Republic, little else was achieved.

Punishment

Soon after, supporting Austria instead of France in the War of the Spanish Succession had dire consequences for Catalunya. The fall of Barcelona on 11 Sep 1714 officially abolished the Crown of Aragón, removed local laws & put the entire region under control of the new Bourbon king. Catalunya remembers the tragic event by making September 11th National Day (La Diada).

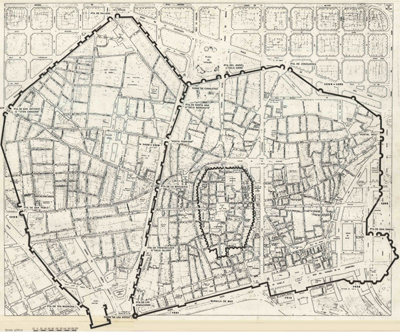

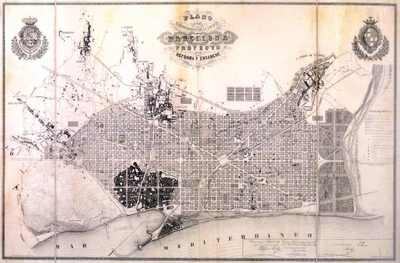

A firm hand along with a gigantic fortress & prohibition to build outside the city walls kept Barcelona under control. Catalunya more or less behaved as Spain desired so Barcelona received permission to tear down city walls in 1854 & expand with fantastic results: the Eixample. Decorated with trendy Art Nouveau, this orderly & artistic expansion transformed Barcelona into a world-class city. Early industrialization provided the wealth that modernisme required as well as funded the nation. According to Robert Hughes, Catalan industry provided over 25% of Spain’s GNP in the mid-1850s. Expansion of the city gave future visitors much to marvel at… just look at the before & after:

Guerra Civil

With the Spanish monarchy obsolete, the Second Republic granted Catalunya its first Statute of Autonomy. The 1932 document officially promoted bilingualism, allowed involvement in legislative & education decisions as well as granted some control over security/defense. In truth, the statute became a watered-down version of the original draft almost unanimously approved by Catalans. But the Spanish Civil War cut its implementation short & Catalunya began making decisions far beyond the agreement. An offended Republic eventually sought refuge in Barcelona, but again Catalunya fell on the losing side. Generalísimo Francisco Franco removed civil liberties & restricted use of the Catalan language.

The degree of restriction seems to be a hot point of debate. I have friends who grew up in Barcelona during the Franco era & spoke Catalán in school & at home. Granted, public speaking of Catalan was prohibited at first but it survived in spite of being treated as a foreign language. A 1962 article titled “The Resurgence of Catalan” claims that in 1953 Franco began to relax controls, prizes were established to encourage works in Catalan & in 1954 the author “counted six hundred books in Catalan, in many different fields, on the shelves of one bookstore in Barcelona.” Hardly the level of publication during the Second Republic but apparently accessible.

As in the Basque Country, Franco also encouraged migration from other regions of Spain in order to dilute the area’s independent character & use of the Catalan language. Certainly a complicated time to live there, but I’m intrigued at the idea of seeing Barcelona with little traffic & no tourists on the Ramblas (below, 1951):

Return of the king

Franco’s death in 1975 provided Catalunya with a unique decision: stay with Spain or break away? They opted to stay. Under the 1978 Constitution, Catalunya is listed as a nationality (whatever that means, certainly not a nation) along with the Basque Country, Galicia, Andalucía & Valencia. The Preliminary Title states:

“The Constitution is based on the indissoluble unity of the Spanish Nation, the common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards; it recognizes and guarantees the right to self-government of the nationalities and regions of which it is composed and the solidarity among them all.”

Ambiguous on purpose, even the definition of what constitutes Spain comes into question. Specifics were to be defined later by individual agreements with each of the 17 regional governments that comprise the nation. The 1979 Statute of Autonomy greatly improved on the first version, & local officials emphasized language as an essential part of Catalan identity.

Jordi Pujol remained in power from 1980 until 2003 as president of Catalunya —that’s 23 of the first 25 years of democracy! His point of view was that whatever was best for Spain was also best for Catalunya, pledging regional support to aid national growth & pushing the issue of independence to the back burner. Robert Hughes wrote in 1992:

“Even though the issue of Catalan political separatism was repudiated by its own State government in September 1991 and now seems politically dead except among a few nostalgists and rhetoricians (it could hardly be expected to survive the real democratic changes of Spain after 1975), the sense of Catalunya as a distinct cultural identity within the larger Iberian body endures.”

While I would contest his political analysis, Hughes offers an interesting observation based on personal experience. My, how times have changed.

Economic crisis

So how did separatism return to the forefront?

Without Pujol’s centrist influence, local politicians revised the Statute of Autonomy. Approved in 2006 with low voter turnout compared to previous referendums, more power devolved from the national government to Catalunya… much to the chagrin of other regions. In fact, several autonomous communities (including neighbors Aragón & Valencia) legally challenged those revisions in Spain’s Constitutional Court. In 2010, the Court rewrote several sections to remove previously approved items of self-government & decreased control over taxation. Tense times.

Effects of the Spanish economic downturn (2008—present) also contribute to the current debate. Boom years fueled by construction made recurrent budget deficits & lack of control over taxation easier to swallow. But with no hope for immediate recovery in spite of austerity measures “recommended” by the ECB, Catalunya feels it could run its affairs better. I don’t doubt that for a second given the number of economic abuses & scandals which have come to public light in the last few years (like the Caso Gürtel or the Caso Bárcenas).

In 2012, the convergence of two events also generated a revival in separatism. Elected in 2010, Catalunya President Artur Mas enjoyed a comfortable position in parliament with 62 of 135 seats, only 6 short of a majority. In order to deliver on campaign promises, Mas wanted to negotiate a new fiscal agreement with Madrid… especially since the tax reforms of the Statute of Autonomy had been reversed by the Constitutional Court. The new proposal, approved by the Catalan parliament in 2012, only needed the unlikely go-ahead from the Spanish President/Prime Minister. Lobbies for independence had also been campaigning heavily at the time & it showed. On National Day 2012 1.5 million people crowded onto Barcelona streets to support independence. Mas’s meeting in Madrid nine days later went horribly wrong & requests for fiscal autonomy were postponed once again.

Mas thought the time was right to use both events to his advantage. Calling for snap elections, his campaign ran on the idea of Catalunya’s “right to decide,” but he misjudged the public. His party lost 12 seats, most handed over to the traditional separatist party ERC. This kept the issue alive but not under complete control by Mas. What’s even more interesting is that a new, non-separatist party (the C’s) went from 3 seats in parliament to 9! Completely contrary to what anyone expected. In January 2013, Parliament approved a Declaration of Sovereignty; however, a referendum scheduled for 2014 about independence may or may not materialize.

Breaking away

Using historical precedent as justification for 21st-century independence seems the least convincing of all arguments. Marriage into the more powerful Crown of Aragón maintained some separateness but certainly not in name. In 1714, elimination of the Crown of Aragón ceded all rule to central Spain. Game over. The 1979 referendum had a voter turnout of 59.7% with 88.1% approval… the majority wanted to remain Spanish. Desire for independence seems to come & go, depending on external circumstances.

On the other hand, if the result of the 2014 referendum —already declared illegal by Spain’s current ruling party— finds that the majority want independence, then they should be allowed to pursue their own path. Being the cash cow for a corrupt government wouldn’t sit well with me either. The resurgence of the Catalan language has solidified their cultural identity. Catalan speakers even have 18% higher wages than non-speakers. But does cultural identity necessarily correspond to nationhood?

I’ve only found one study concerning the economic viability of an independent Catalunya. Maintaining current levels of taxation, it concluded that the new nation could survive on its own even after establishing embassies, renegotiating contracts & developing social welfare programs. What currency would be used? Goodbye Spain, goodbye €. Even if Catalunya is put on a fast track to join the EU/€ zone, there would likely be a period of limbo, not to mention the cost & hassle of changing to another currency then back to the €. Vice-President of the European Commission, Joaquín Almunia, stated on 17 Sep 2013:

“If one part of a territory of a member state decides to separate, the separated part isn’t a member of the European Union.”

Not necessarily what separatists want to hear, but that’s the difficult reality of their demands.

Many wonder if the transformation of Spain into a federal nation would resolve most issues with Catalunya & save the country as a whole. Or would taxation reform alone do the trick? Election results show that some feel a need for complete rupture while others only want more room to maneuver within the current context. I’ve always liked the idea of self-determination, but separation might cause a ripple effect with the Basque Country & then what? Would regions in other EU countries follow? It will be interesting to follow this issue in the near future since it impacts more than just residents of Catalunya or Spain.

Update (12 Dec 2013): The date for the referendum has been set for 09 Nov 2014. The questions proposed will be two instead of one… A) Do you want Catalunya to become a State? Yes or No? B) If so, do you want that State to be independent? Yes or No? But Mas says he will only go ahead with the referendum if the central government approves. Unlikely at this point.

Update (10 Nov 2014): As expected, emotions ran high during the months leading up to the vote. But no one thought yet another scandal would bring Catalunya’s grandfather of politics, Jordi Pujol, back into the spotlight. As President of Catalunya for 23 years (!) from 1980 to 2003, Pujol promoted Catalan integration into Spain, and more broadly, into a united Europe. In July 2014, Pujol revealed that he had kept a large inheritance from his father in secret bank accounts for the past 34 years… avoiding taxes & raising suspicion of money laundering. He stated that there was “never a convenient time” for declaring the fortune. During an interrogation by the Catalan parliament Pujol became belligerent & yelled that he was not a corrupt politician. The investigation of 100 million € floating between tax havens in Switzerland & the Cayman Islands (among others) may prove him wrong. But as the political father figure for the current president, Pujol’s confession had a negative impact on the independence movement.

In October 2014, disagreements among the pro-independence political parties, President Artur Mas & Spanish PM Mariano Rajoy came to a head. Mas retreated, saying that the vote would continue as scheduled but it would be more like a survey or poll rather than a referendum. No one on either side of the issue seemed pleased, & Mas’s influence in local politics reached an all-time low.

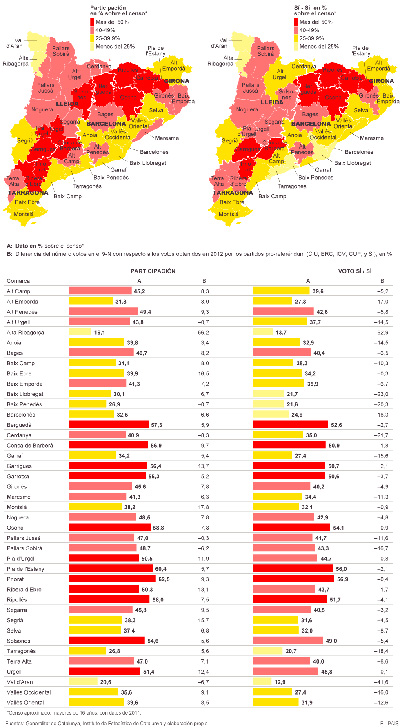

Local venues staffed with volunteers held an unofficial poll on 09 November as planned. In fact, the urns will remain open until the 25th! Voting age was dropped to 16 in order to increase the number of voters & Catalan residents abroad were encouraged to vote overseas. Figures so far show a turnout of 35% of the population eligible to vote with 81% in favor of independence. The info graph from El País (in Spanish) shows both turnout & poll results by region. Even with low voter presence, the large portion of sí votes has at least restored some political power to Mas. How Madrid reacts will be seen soon, as Rajoy is set to address the issue tomorrow.

Of course, we’ll update this post periodically as the issue unfolds… well, I thought I would. But the issue has become so complex that at least this post serves as a good intro to the independence movement in Catalunya.

Want to learn even more? Download this Word document for a complete bibliography of articles consulted while researching this post.