In an continuing effort to understand what makes Buenos Aires tick, I began investigating a few events that had significant historical impact yet are not represented or remembered in the collective consciousness. Once again, “The Collective Memory Reader” comes in handy.

Peter Burke states: “Some cultures are more concerned with recalling their past than others.” Perhaps that’s true in Argentina’s case. They certainly do a good job with recalling independence leaders, but the 20th century seems to be almost taboo… too close to the present, too much unresolved conflict & still searching for national traditions that apply to everyone regardless of political affiliation. At the end of the 19th century when most nations were creating traditions/identity, Argentina had just come out of decades of internal conflict. Then the immigrants arrived. Seems like they didn’t have a chance to join the trend.

It also seems there is little sense of nostalgia in Argentina, perhaps as a result of their political “newness” as mentioned above. I’ve never heard the equivalent to “Ahhh, those were the good ol’ days,” so does an attraction to a real or imagined past exist? Either are valid, but what era or period to choose? Argentines were rightfully proud of the fact when they were the granero del mundo & fed everyone. But it seems like selective memory wins out over collective memory given the turbulent times of the 20th century.

The following events took place in Buenos Aires, but find no physical presence to remind today’s porteños or visitors of their occurrence:

#1: Assassinations of Varela & Wilckens

Last year after reading “La Patagonia Rebelde” by Osvaldo Bayer, it seemed odd that there was no attempt to commemorate the victims in Argentina’s capital. And not everything happened in Patagonia… two important events actually occurred in Buenos Aires.

The very abbreviated version: In 1921, striking ranch hands in Santa Cruz requested better working conditions & thought they would be successful based on a similar strike the previous year. President Hipólito Yrigoyen gave Lt. Héctor Benigno Varela free reign to take care of the problem. Varela’s solution ended the strike when the army killed 1,500 workers in a region-wide manhunt… often luring strikers with the promise of negotiation but shooting them point blank instead. Yes, this is during a “democratic” period.

Back in Buenos Aires, Varela was lauded a hero by the upper class, but anarchists & union sympathizers were not pleased. In 1920, Kurt Gustav Wilckens arrived in Argentina. Born in Germany, Wilckens had first-hand contact with rural workers while on a ranch in Río Negro. Seeing Varela as the perfect example of a system gone wrong, Wilckens waited outside Varela’s house in Palmero (Fitzroy 2493). When Varela exited, Wilckens threw a bomb at the officer & shot him four times. Varela couldn’t even make it to the pharmacy next door.

Wilckens protected a 10-year old girl who wandered into the scene, so he too was injured by the bomb blast. Placed in the federal penitenciary, Wilckens in turn was murdered by elite supporter, Jorge Ernesto Pérez Millán Temperley, who snuck into the prison just to murder Wilckens. Pérez Millán was later killed by an anarchist while serving time in the same prison.

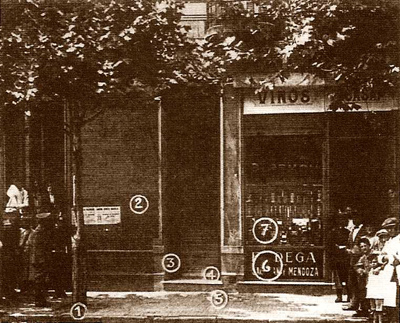

Caras y Caretas thought the events were so shocking that they staged a reenactment of the assassination (Año XXVI, No 1270):

Today both Varela’s house & the original pharmacy have been demolished… replaced by the building seen below. A confitería occupies the lot where Varela once lived, but no plaque or other reminder of the events can be found. The prison was demolished decades ago to make way for Parque Las Heras. The fact that it is now a public space makes it a perfect spot for some kind of memorial… but it must not be important enough.

#2: Capture of Adolf Eichmann

As an SS officer, Eichmann was responsible for implementation of the Final Solution in Poland & Hungary. He managed to escape from the Allies & obtained a passport via an odd but well-documented connection between the Perón government, the International Red Cross & the Vatican. Eichmann lived outside the city limits of Buenos Aires from 1950 until 1960, brought his family to Argentina & worked in a wide variety of jobs to support them.

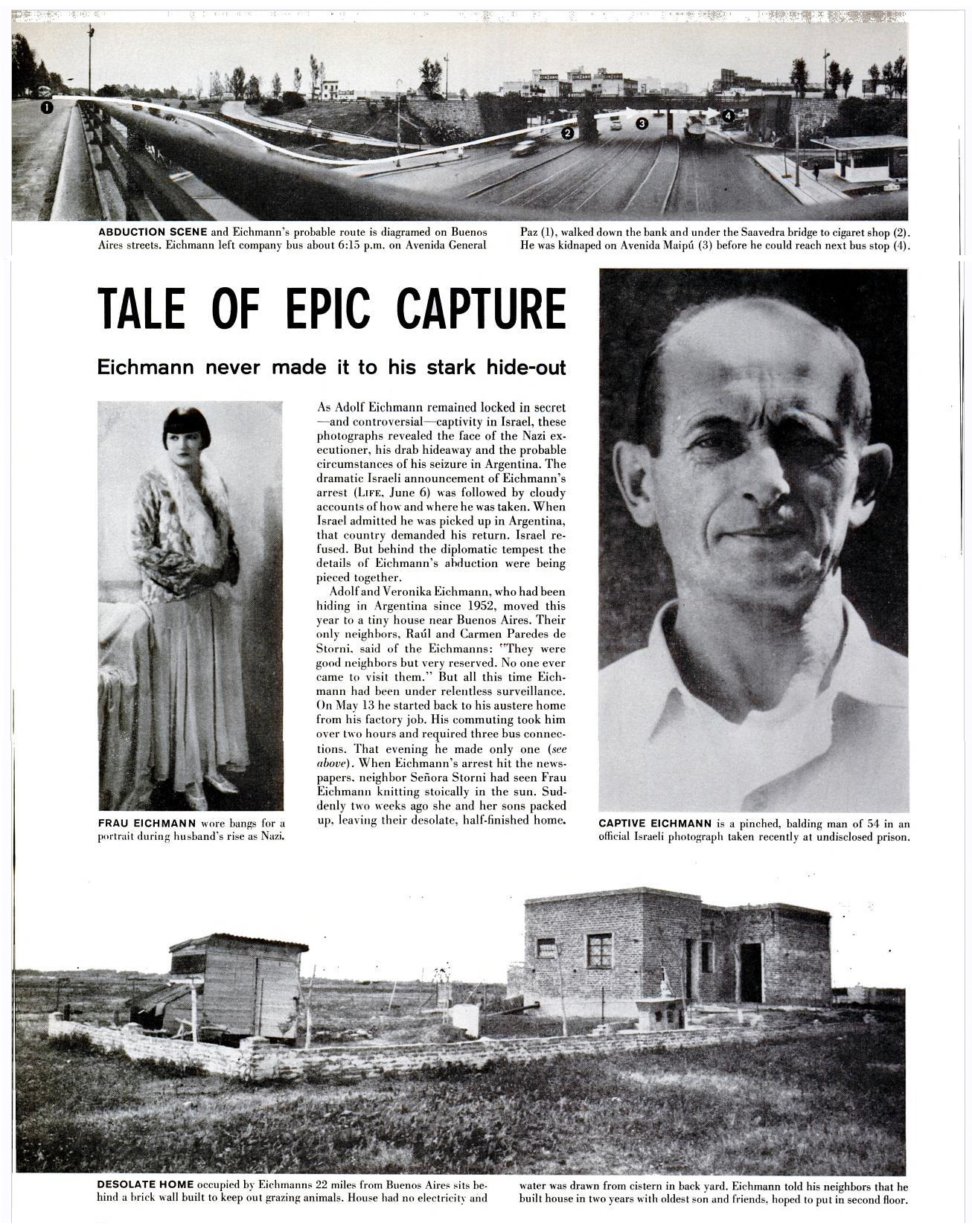

Mossad agents discovered Eichmann & captured him on Avenida General Paz as he was going home from work. Illegally smuggled to Israel while drugged & disguised as a flight attendant, his trial drew international attention. Eichmann was sentenced to death & hung in 1962.

LIFE magazine covered the capture of Eichmann (20 Jun 1960, Vol. 48 No. 24), calling it “epic.” It certainly was.

From their report & panoramic photo, I deduced the location of Eichmann’s abduction. Avenida General Paz has been widened since the 1960s, making it difficult to find the exact spot. And the Federal Police have a mini-hut set up under the highway with a single officer. He immediately made the standard request for no photos. But since he was only about 20 years old, I decided to chat with him. He knew nothing about Eichmann but was more than interested in why a yanqui was living in Buenos Aires 🙂 I never got his permission to take photos, so I had to sneak the following from behind a post. There’s absolutely no reminder of the event:

#3: Acts of violence during El Proceso

Crimes of the last dictatorship have been discussed at length during the last decade. Clandestine torture centers have been exposed & a monument to the desaparecidos has even been built. Great. But the late 1970s were very violent, & there is little reminder of that dark period around the city.

For example, the photo collection “En negro y blanco: Fotografías del Cordobazo al Juicio a las Juntas” (2006) shows the aftermath of a bomb at the intersection of Uruguay & Guido. Today it’s odd to think this kind of violence happened in the swanky barrio of Recoleta. The faux well has been replaced, but the intersection looks pretty much the same as in December 1977 when the bomb exploded:

There may be no plaque to remind passersby of what happened there, but just take a look around… damage to the adjacent building is still very visible. But who would know this was the result of a bomb detonated by armed dissent groups??

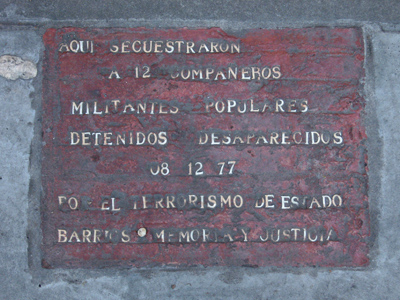

At least local residents have been more responsive than local or national government by placing hand-crafted sidewalk memorials in front of buildings where desaparecidos were abducted:

Understandably, there are events which every nation chooses to exclude from collective memory. But hopefully those mentioned above (plus many others) will find their way into the public realm once again… more food for thought.

El caso Penjerek. Toda la adolescencia y juventud propia y de muchas mujeres más estuvo signada por este horrible caso que disparó la alarma entre nuestros padres y cambió la forma inocente y crédula conque nos divertíamos y salíamos.

http://www.clarin.com/crimenes/Todavia-hoy-creo-cadaver-Norma_0_707929271.html

Increíble… no sabia del caso. Supongo que lo pueden abrir de nuevo, no?

I am very surprised by your comments that there are no equivalents of the nostalgic ‘those were the good old days’ type reflections in Argentina. I teach English in companies here (just for something different) and it is a constant refrain amongst my middle-aged students – mostly based around the middle class obsession with ‘security’, which considering the bomb blasts and disappearances of the past is pretty confusing for a foreigner, and I can only suppose means that during those golden years only people who got mixed up in politics got a raw deal, whereas now anyone can get shot in a botched 10 peso robbery…

Hi Claire – Thanks very much for the comment. I probably should have elaborated more in that particular paragraph… I was a bit hasty in jumping to the examples. My main question is: if someone does mention that they long for the “good ol’ days,” what period would they refer to? When did everything go so wonderful for Argentines that they would collectively recall a certain period? For example, many Americans consider the post-WW2 era ideal. In spite of the Cold War & somewhat stifling social conformity, the 1950s brought economic prosperity, suburbia & an overall comfy standard of living. We know better now, but I think that decade still generates a certain sense of nostalgia even in Americans like myself who did not live during that time.

The media frenzy over inseguridad has certainly driven many middle-class people to yearn for earlier, “better” times. But I doubt given the opportunity they would want a return to the late 70s or early 80s. I think it’s more of a generalized plea for less-troubled times in the present rather than strong reminder of one particular era in the past. Would you agree based on what your students say?

According to the biography in the book “Hunting Eichmann”, the Mossad agents made detailed reconnaissance trips to his home in San Fernando. They even drew a map, showing multiple land marks where his house was, on Garibaldi Street, between Gondolfo and what they referred to as a stream or arroyo, as well as RP202/Ipolito Irigoyen and Pedro Leon Gallo. The entire area has changed a lot since the incident (it was almost entirely open fields), but the major land marks are still there, including the train track where the agents surveillance of his nightly routines of getting off the bus and walking home occurred a few blocks away. If all or part of Eichmann’s house is still standing, it has been covered and surrounded by other families homes. From the drawing and photos of the house, the approximate location may correspond to a section on the Google map showing a house with a green roof. If you go to Google maps, you can find a very good mapping of the area.

Thanks for the additional info, Rollie! Keep in mind I wrote this post in 2012 when foreign books were almost impossible to get in Argentina, & Google hadn’t mapped the area well. I doubt any of Eichmann’s house is standing because of the development in the area. But the area I photographed corresponds to the LIFE magazine article. I no longer live in Argentina, so someone else will have to take up the research 🙂

One part of the book that did not get much attention was his obsession with the ABC biergarten. I think this is the ABC Restaurant at 545 Lavalle. If you see their business photos, if appears to be a small restaurant started in 1929 straight out of Austria, but right in the middle of Buenos Aires. I have to assume the heavy German population is due to the similarity between the two countries climates (mountains, rain, etc.) as well as the political issues of the time. I appreciate you returning my replies. Have a great day.

That’s an interesting find… I never went there although what many consider to be the best German restaurant in BA is Edelweiss. The decor is straight out of mid-20th century Germany. I wouldn’t be surprised if Eichmann knew that place as well. The majority of Argentina’s population is of European descent, so Germans would have found there way there as well (even if the predominant groups were Italian & Spanish). BA is subtropical & humid but the mountains of Patagonia certainly reminded them of Europe. Thanks for the info!