No one expected second son José to inherit the throne of Portugal, but his older brother died the year of his birth & José moved to the top spot. He married Mariana Victoria of Spain at the age of 15 who shared his love for hunting & opera… but she never cared much for his affairs!

Crowned king in 1750, José I continued to enjoy a carefree life; most administrative decisions fell to Prime Minister Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo. Later granted the title of Marquês de Pombal, Carvalho e Melo rebuilt the city of Lisbon after a devastating earthquake-fire-tsunami combo destroyed the capital in 1755.

José I developed an interesting side effect from seeing such devastation first-hand. He never again wanted to live in a space surrounded by stone, so the court moved to a complex of tents & wooden structures on the hillside of Ajuda, north of Belém. And in spite of having eight children with Mariana Victoria (half were stillborn), José I had no male successor. He declared his first-born daughter heir to the throne —defying centuries of tradition— while royal families hoped to change the king’s mind… to no avail.

One of the most influential families in Portugal had a close connection to José I via his favorite mistress, Leonor de Távora. In 1758, José I took an unmarked carriage to the royal camp in Ajuda after spending the evening with Leonor. Two or maybe three men attempted to murder the king en route, shooting him in the arm & also wounding the driver. Both returned safely, but the Prime Minister was outraged. He investigated immediately, found two of the assailants & had them tortured to reveal information. They claimed to have been hired by his mistress’s family who wanted their relative, the Duke of Aveiro, on the throne after José I. The men were hung the next day before any public announcement was made about an attempt on the king’s life.

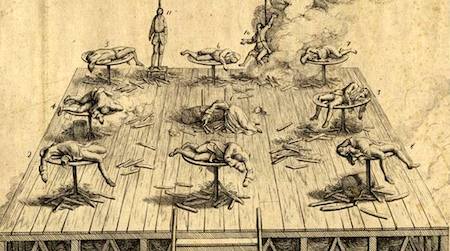

Carvalho e Melo had all members of the Távora family arrested for conspiracy (even the grandchildren!) as well as the Duke of Aveiro & Leonor’s personal confessor, a Jesuit priest. Many were tried for treason, convicted, then publicly tortured & killed. Others spent time in jail or were forced to join religious orders to keep them away from the public & from politics. Mariana Victoria managed to save some younger members of the family, but historians have long questioned whether the Távoras were indeed responsible for the attempted regicide. The family professed innocence while never trying to flee Portugal & certain punishment. Many think Carvalho e Melo merely eliminated some of his most despised enemies. Whatever the reason, José I granted him the title Count of Oeiras for his swift handling of the situation.

Royal officials demolished the mansion where the Duke of Aveiro lived & even salted the ground so nothing would ever grow there. Today, a reminder of this important historic event sits hidden behind snack bar Pão Pão Queijo Queijo. Marked by an asterisk on the page 111 map, a ringed column with a chilling description sits out of sight:

In this place were razed to the ground and salted the houses of José Mascarenhas, stripped of the honors of Duque de Aveiro and others, convicted by sentence proclaimed in the Supreme Court of Incon dences on the 12th of January 1759. Brought to Justice as one of the leaders of the most barbarous and execrable upheaval that, on the night of the 3rd of September 1758, was committed against the most royal and sacred person of the Lord Joseph I. On this infamous land nothing may be built for all time.

The Igreja da Memória is another reminder of the assassination attempt on José I, built on the very spot where his carriage was attacked. King José I commissioned this church two years after the event to show gratitude for his survival. But due to economic problems from the reconstruction of Lisbon, the church had only been half built by the time of his death in 1777. Construction finished 11 years later, when clergy consecrated & opened the Church of Memory to the public.

Its architecture is easy to appreciate with no surrounding buildings to impede the view. Bolognese architect Giovanni Galli da Bibbiena —who died while working on the church— certainly drew inspiration from the Baroque master, Francesco Borromini… love the bell tower placed in the rear! Portuguese architect Mateus Vicente de Oliveira, better known for the Palácio de Queluz & the original layout of the Basílica da Estrela, finished the project by adding a Neoclassical dome. Lots of windows illuminate the interior, & a simple, crowned Portuguese coat-of-arms high above the main entrance lets the casual passerby know that this church had special importance to the royal family.

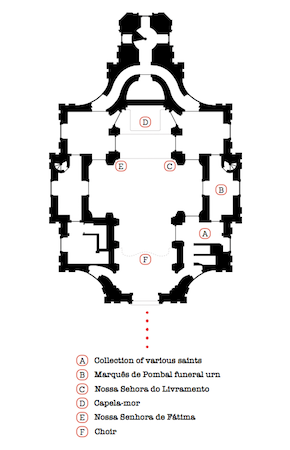

Although the compact interior reduces worship space to a minimum, the high, central dome adds breathing room. Colors from pink & blue stonework along with an abundance of gold leaf also make the space feel lighter. Don’t miss views from the upper balconies & connected choir.

Depending on your time of visit, the trono eucarístico may be on display or perhaps hidden behind a painting of José I thanking Mary for his salvation. The Baroque era incorporated theatrical elements into design, & this dual-function altar is unique in Lisbon. In 1985, a bolt of lightning destroyed the lantern tower crowning the dome with repair work continuing for the next couple years —including installation of a lightning rod. Restoration continued during the 1990s, but filtration from the roof has damaged the ceiling once again.

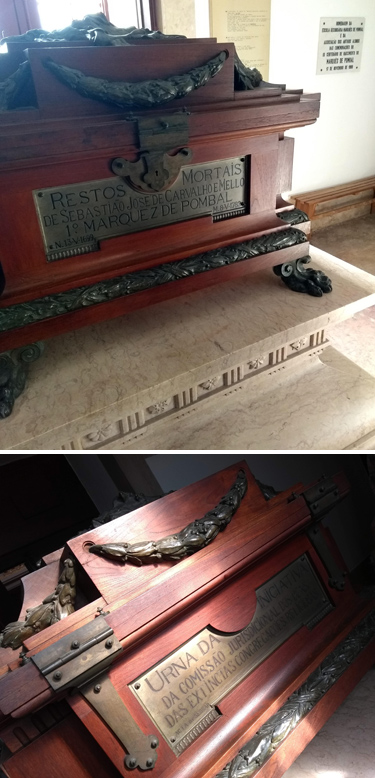

Currently the Igreja da Memória is the official church for the Ordinariato Castrense, a religious body serving the military as well as national security forces of Portugal. They often hold special services for personnel here. However, the most significant historical tidbit about this church is that the remains of the Marquês de Pombal were placed here in 1923. Carvalho e Melo died in the village of Pombal a few days short of his 83rd birthday in 1783. Absent from any position of power & banned from the presence of Queen Maria I, he was initially buried in the village… but the Marquês de Pombal would hardly rest in peace.

During the Napoleonic invasion of the early 1800s, French troops desecrated his tomb. What few remains that survived found their way to Lisbon. Placed inside the Mercês chapel in Bairro Alto, Carvalho e Melo returned to the same street where he had lived during the most influential time of his life. But when that chapel was demolished in 1923 to construct a residential building, his remains came to this church. Due to so many changes of location & the Igreja da Memória being closed to the public until 1951, most lisboetas have no idea where this once powerful figure finally found a permanent home. If the room is closed, try opening the door or ask to see inside. Someone will be glad to assist.

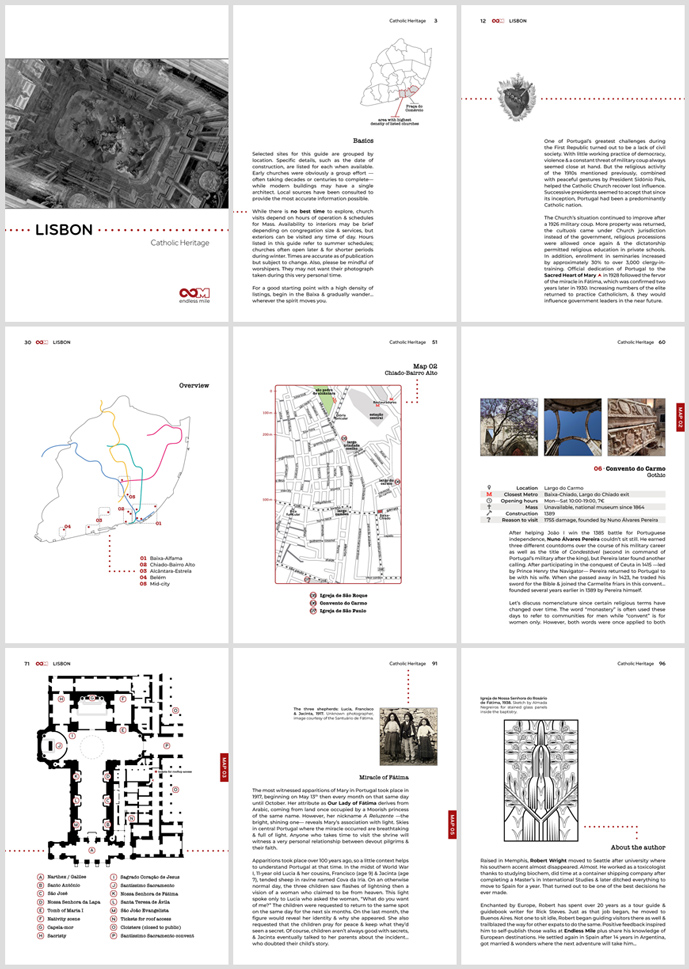

If you enjoyed this post, imagine how great our Catholic Heritage guide would be on a visit to Lisbon! The Igreja da Memória is one of 12 sites discussed in detail. Don’t worry if you’re religious or not… this guide uses Catholic heritage as a vehicle for discussing current events, important national history & the ever-changing relationship between church & state in Portugal. Consider it a respectful religious guide written for a secular audience. As always, thanks for your support!

Hi Robert,

Congratulations on your new guide book. I wish you much success with it. Really enjoyed reading this post. Your research is impeccable and interesting and your photographs are really wonderful, too. Looking forward to more.

Abraços,

Emanuel

Thanks, Emanuel! When you are back in Lisboa, let me know & I’ll send you a free copy of the guidebook. Perhaps it will help show you more of one of my favorite cities. Take care & stay safe, um abraço!

That’s very kind of you but I think I should buy your guide. There’s little ways we can still support each other in today’s crazy world.